Science doesn't prove things

We find “proof” to be comforting.

Mathematicians use proofs to establish truths that they can then build upon, incrementally adding another room or floor to the tower of mathematical knowledge.

The military uses it (via “proving grounds”) to verify that the weapons, tactics, and personnel are reliable and sufficient to be “combat-ready” — that the leadership can rest assured that the units and weapons they deploy will be able to accomplish (to the best of their ability) the strategic goals given to them.

Even in legal contexts — if you are to be accused, and subsequently convicted of something, the prosecution must meet the “burden of proof”; commonly said as “proved beyond a reasonable doubt”.

We like to know that when we say, think, or believe something, that we’re not placing our confidence poorly. It’s embarrassing to be wrong. Proof is reassuring because we can be confident in our beliefs.

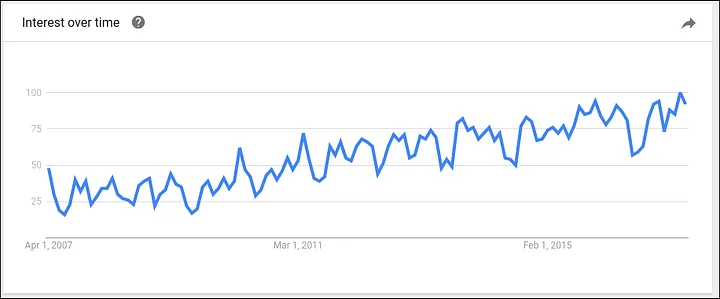

Over the past 10 years, the occurrence of the terms “proves that” have been increasing. I don’t mean this to be indicative of anything other than its face value (that is to say — I am not suggesting this “proves” anything). It does reasonably suggest, in my opinion, that discussing how something “proves that” something else is true is an idea that has been increasing in popularity. My hunch on this is that it makes for good clickbait. (“Scientific research proves that dog owners are happier and make better lovers!”)

But science, both lowercase “s” (the subject) and uppercase (the “institution of”) don’t “prove” things. It’s not that they have tried and failed, it’s just that’s not how science works.

Carving Away

My last semester of my undergrad (I was an interdisciplinary Science & Math major), one of my professors described the “process of Science,” and I had been reading about this idea elsewhere as well. I don’t remember specifically where this analogy comes from so I don’t have a citation, but I don’t need to claim the idea as mine — it bears repeating regardless:

Imagine a massive block of marble before you, representing every possible thought, concept, idea, or explanation for the universe of the natural world. Within this block is the statue of David, which represents the “truth” about that universe.

The process of science is to chip away at the parts of that block that we can show are not part of that statue. We use the scientific process to disprove the thoughts, concepts, ideas and explanations that are unfit to be part of our “David.” The more that we refute, the more that we reveal about the true nature of things.

Experimentation is how we examine whether a particular bit of marble (“an idea”) is part of the statue (“the idea is supported by this experiment”) or is destined for the bin (“the experiment fails to support this explanation”). With enough experimentation, enough examination of these ideas, we can separate the chaff from the wheat. (The disease “malaria” was originally thought to be the result of “bad air”, for example)

Well-meaning articles about this or that being “proved” by scientific research suggest that we are sculpting “David” out of clay — that we are building a tower of proofs as a Mathematician would do, or showing evidence beyond doubt that we can hold conviction from our accusations of the natural world. The “proving ground” may well be the most fitting analogous use of “proof”, of those three, because it’s an eliminating process.

Uncomfortable Uncertainty

“Proofs” are comfortable, and so by extension we might feel “uncomfortable” in their absence. It feels far more comforting to say “their research has proven that cauliflower prevents cancer” than to say “their research found that people that frequently consumed vegetables in the same family as cauliflower had less incidence of cancer.” But we lose something in the simplification. The certainty and confidence of the former statement is so alluring and sexy, but it’s inaccurate. One of our metaphorical David’s fingers is present somewhere near that research paper — there’s clearly something to be explored further with that — but our confidence about which finger, or its shape, requires us to chip away at more of the marble first.

The flip-side of this is that when scientific publications show you the metaphorical David’s elbow, and say “we’ve found the bicep and the forearm, and have eliminated the marble underneath, this is definitely an elbow,” we should feel more confident in accepting “ok yeah, I see what you’re pointing to.” Even if we don’t know what if his elbow is pointy or rounded, or how muscular his bicep really is, it’s clearly an elbow. (Sidebar: the link in that paragraph is a lot of reading, but has good data and conclusions within it. It can be challenging, but this is a complicated subject area)

Finding our keys in the dark

Today, on Earth Day 2017, tens of thousands of scientists are marching on Washington D.C. in protest of the administration’s aggressive stance against science and research that might otherwise be…problematic…for private sector ventures.

The process of science, of chipping away at that block of marble, can be counter-intuitive, especially given how journalists constantly munge the details when trying to make interesting articles. Politicians that wish to enact (or remove) policies that disagree with scientific consensus will try to leverage this confusion against the public, or convince the public that they have the answer with 100% certainty, which is a heck of a lot more appealing, even if it’s ultimately wrong.

There was a joke I read a while back that seems fitting:

I was downtown having a drink with some friends. After a few rounds and some laughs, we left the bar to wait for our cab to arrive. About 10 feet away under the stark light of the street lamp, was a man crawling around on the pavement and sidewalk, clearly looking for something.

“Hey — you okay? What are you looking for?”

The man paused and looked up, “I’m trying to find my car keys.”

My friends and had some time before our cab arrived, so we started to look with him. We looked all around the car, the tires, in the sewage grates, under the nearby mailbox, even near the entrance to the bar. No one found the keys.

“Where’s your car? Maybe they fell out of your car when you got out.”

The man gestured with his thumb, behind him, “it’s a block away, that way.”

My brow furrowed. “Why on earth are you looking over here, then?”

“The light is better over here, I don’t like the dark.”